Data Engineering Components: Kubernetes Explained

Note: Kubernetes is a tool for orchestrating Docker containers. If you’re not familiar with Docker, I recommend you read this article first.

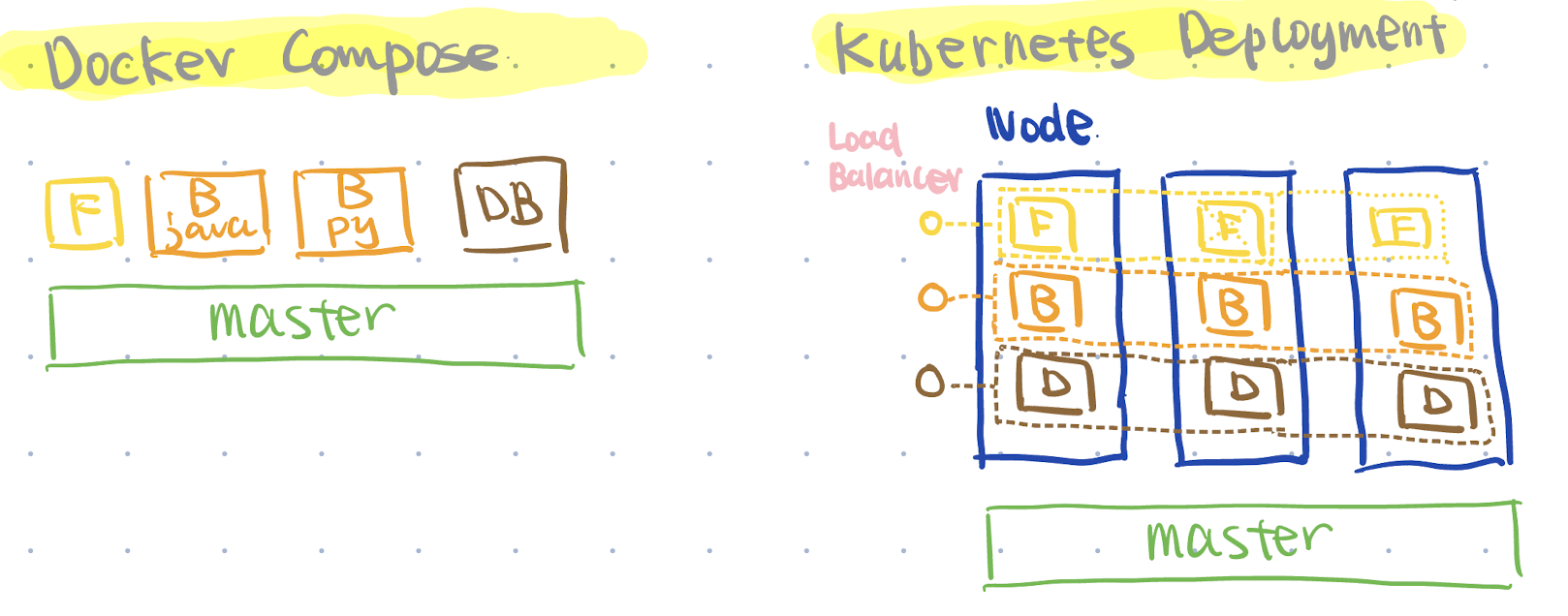

Assume we have three Docker containers: frontend (React), backend (Python), and database.

We can use docker compose to manage dependencies among these containers. For example, we can specify that the backend container should start after the database container.

version: "3.8"

services:

frontend:

# Build the frontend image using the Dockerfile in the 'frontend' folder

build: ./frontend

# Map port 3000 in the container to port 3000 on the host

ports:

- "3000:3000"

environment:

# Let your frontend know where the backend is running.

- REACT_APP_BACKEND_URL=http://backend:5000

depends_on:

# Ensure the backend service is running before the frontend

- backend

backend:

build: ./backend

ports:

- "5000:5000"

environment:

# Example of passing database connection info to your backend; adjust if needed.

- DATABASE_URL=postgresql://root:root@db:5432/ny_taxi

depends_on:

# Ensure the database is running before starting the backend

- db

db:

image: postgres:13

environment:

- POSTGRES_USER=root

- POSTGRES_PASSWORD=root

- POSTGRES_DB=ny_taxi

volumes:

- ./ny_taxi_postgres_data:/var/lib/postgresql/data

ports:

- "5433:5432"

However, there is still an issue: what if the business grows and we want to scale up the number of containers to handle increased requests?

Using docker compose, we’d have to manually manage container scaling.

As we’ve discussed before, developers won’t like repetitive tasks. They prefer describing the desired state (refer to the declarative approach explained in the Infrastructure as Code section) and letting tools handle container deployment and management.

This is where Kubernetes (also called K8s, since there are eight letters between ‘K’ and ‘S’) comes in.

Benefits of Using Kubernetes vs. Docker Compose

Note: This part is based on my personal understanding of this video: Container Orchestration Explained

- Deployment Management:

- Scheduling: K8s has a scheduler in its super brain, which automatically finds suitable nodes with enough resources to run pods, making sure workloads are efficiently distributed across the cluster.

- Auto Scaling: When certain features are enabled and if you request too many pods, K8s can add new nodes by sending requests to your cloud provider to run these pods.

- Automated Recovery: If certain containers go down, K8s has self-healing abilities and automatically launches new containers.

- vs. Docker Compose: Docker Compose is used to run multi-container Docker applications directly on a single host, meaning it only utilizes OS resources and does not support advanced orchestration features provided by K8s.

- Networking:

- Internal Networking: Every pod in Kubernetes gets its own IP address, and a specific service (via ClusterIP) can be accessed by other internal services using the cluster IP.

- External Access: Kubernetes can expose services to the outside world using services like Load Balancer, which can distribute external traffic across healthy pods.

- Insights:

- K8s can integrate with tools such as Prometheus for detailed logging and analytics, and Istio to provide insights into how microservices interact.

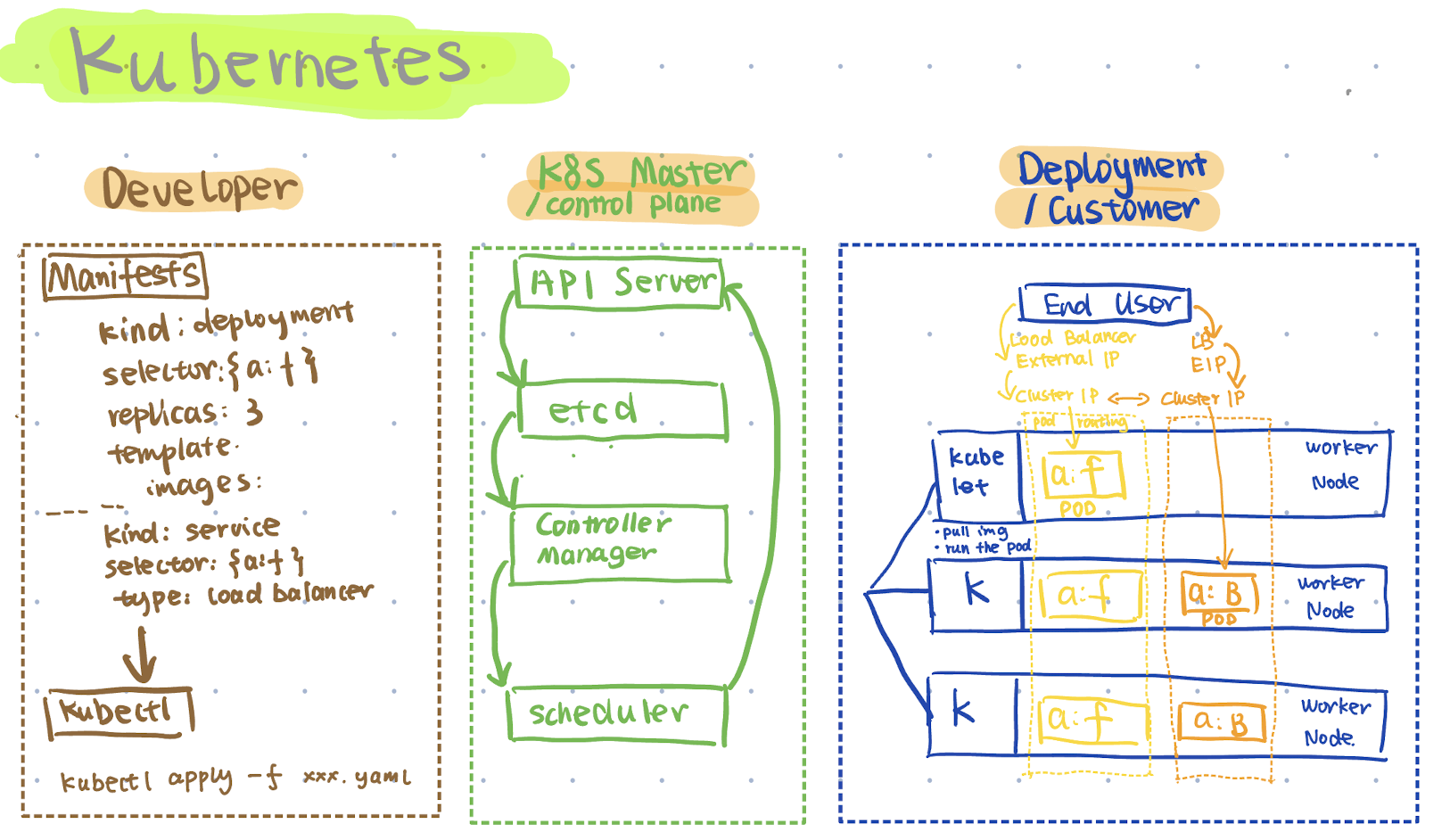

Kubernetes Architecture

Note: This part is based on my personal understanding of this video: Kubernetes Explained

Developer Side: Define the Desired State

In the first stage, developers describe the desired state and relevant settings in a configuration file, which Kubernetes calls a manifest.

Generally, we define the Deployment section—such as how the application should run, the number of replicas (pods) to maintain, the container images to use, and update strategies.

In this example, we define a pod template with two containers labeled app: frontend, and we specify that we need three replicas of this pod.

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: example-deployment

spec:

# Create three pods labeled app: frontend

replicas: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

app: frontend

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: frontend

spec:

containers:

# Only run multiple containers in one pod when the containers are tightly coupled

# Example: Running two containers in one pod

- name: nginx

image: nginx:latest

- name: nodejs

image: node:latest

Once the manifest file is ready, we use another component called kubectl, whose primary role is reading the manifest and sending requests to the control plane (K8s master) through an API.

To use kubectl, we typically run: kubectl apply -f <manifest_filename> (other commands will be discussed later).

Control Plane: The Kubernetes Master (“Super Brain”)

The super brain is mainly responsible for ensuring the actual state on the deployment side equals the desired state from the developer side.

In the previous step, kubectl processes requests by reading the manifest and sends these requests to the API server in the control plane.

The API server records the desired state, such as having 3 pods, into etcd, a key-value store for the cluster.

Next is the controller manager, responsible for managing controllers such as nodes, services, and replica sets. It also interacts with cloud provider APIs, enabling easy provisioning of services like load balancers or persistent storage.

The scheduler continuously monitors etcd (via the API server) for new pods that haven’t been assigned to nodes yet. It evaluates available resources and assigns pods to appropriate nodes.

The scheduler also sends back requests to the API server to trigger deployment.

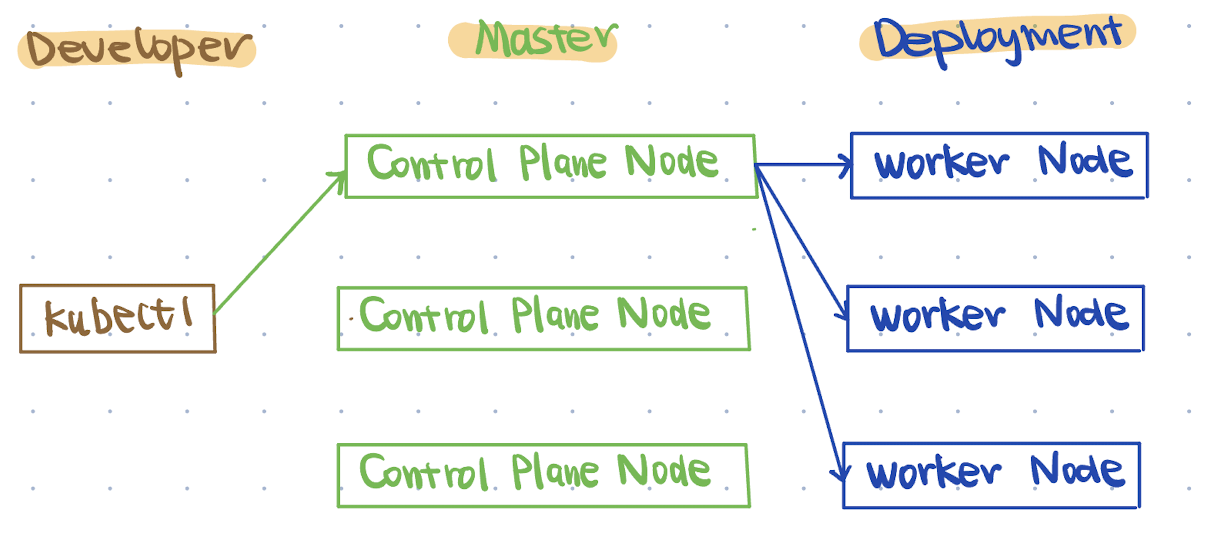

Advanced: Highly Available Control Plane Nodes

In the production environment, we can set multiple control plane nodes to avoid potential failures. The kubectl sends requests to one of the control plane nodes using the load balancer.

The selected control plane node internally processes the requests using API server, etcd, etc., and manages all the worker nodes in the deployment side.

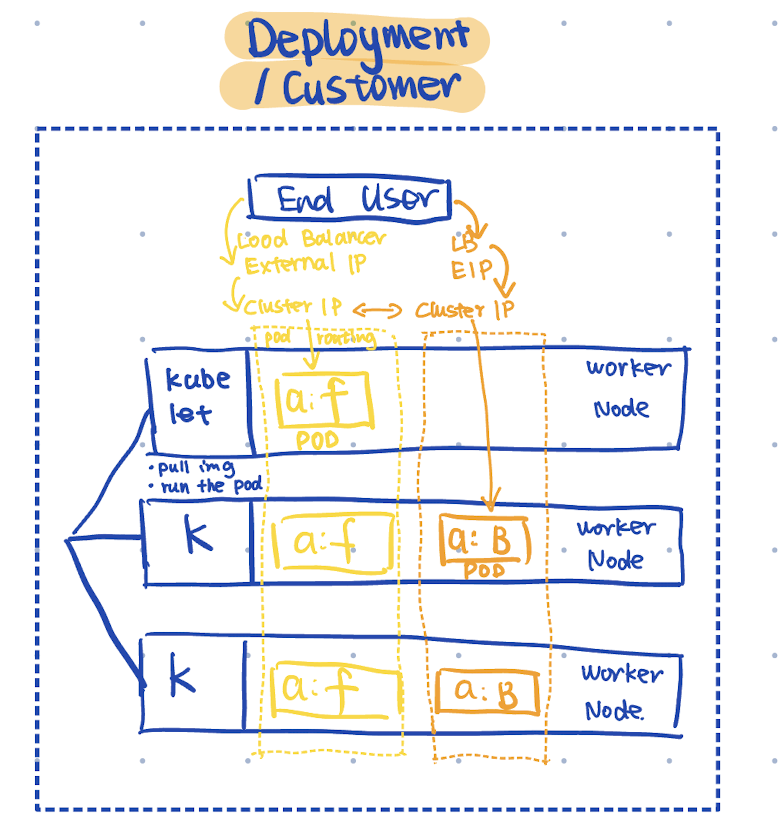

Deployment

On the deployment side, there’s a component acting like a “doorman” called kubelet, constantly watching the API server.

When changes are detected and commands are received, the kubelet runs pods according to the manifest, such as pulling the specified images.

After containers start successfully, kubelet reports back to the API server, indicating pods are now in the “Running” state, allowing etcd to update the cluster state.

In the diagram, the three pods share the selector app: frontend (shown as a:f), forming a service within Kubernetes.

While pods themselves are ephemeral and can be stopped and recreated at any time, the services are not ephemeral. They remain consistent and expose network connectivity.

Internally, the frontend service interacts with the backend cluster via the cluster IP.

If we want to distribute traffic among containers, we can add the following configuration in the manifests.yaml:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: frontend-service

spec:

type: LoadBalancer

selector:

app: frontend

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 80

targetPort: 80

This way, external users can access the frontend cluster by sending requests to the load balancer’s external IP. The load balancer then forwards those requests from its external IP address to the frontend cluster.

Hands-on K8S

Write Your Own Manifests

In the beginning of the manifest, we can define the kind. There are some common kinds we need to define, including the app type, networking, and storage.

Workloads: Deployment vs. StatefulSet

Generally, there are two types of workloads.

- Deployment: which means they are stateless apps, like a search engine. No matter how many pods you specify, K8s will create them at once, and a random identifier will be assigned by K8s.

- StatefulSet: which corresponds to stateful apps, like a database backend. Pods are created sequentially, e.g., pod-0, pod-1, pod-2, and when scaling down, the pods created later will be deleted first.

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

or

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: StatefulSet

After defining the kind, we need to define relevant features of the Deployment or the StatefulSet:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: example-deployment

labels:

# Can be different from the other two

# Usage: kubectl get deployments -l app=frontend

app: frontend

env: production

spec:

replicas: 3

selector:

# Must be a subset of spec.template.metadata.labels

# Used internally by the K8s control plane

matchLabels:

app: frontend

env: production

template:

metadata:

# Used together with spec.selector.matchLabels by the K8s control plane

# Usage: kubectl get pods -l version=v1

labels:

app: frontend

env: production

version: v1

spec:

containers:

- name: mycontainer

image: myimage:latest

ports:

- containerPort: 80

It might be confusing with lots of labels coming along. The key to remember is that the Deployment’s selector (defined in spec.selector.matchLabels) must match a subset of the pod’s labels (in spec.template.metadata.labels).

The K8s control plane (controller in detail) uses the labels defined in spec.selector.matchLabels together with the labels in spec.template.metadata.labels to determine which pods it should manage.

Here are the differences explained in detail:

- Deployment Metadata Labels: Not used for pod management; mainly for Deployment management and organization. You can use them like

kubectl get deployments -l app=frontendto filter relevant deployments. - Selector Labels: Internally used by the Kubernetes control plane to define which Pods the controller should manage; must be a subset of the Pod Template Labels.

- Pod Template Labels: Used to manage Pod labels and also by the control plane. You can use them like

kubectl get pods -l version=v1to filter relevant pods.

Networking: LoadBalancer vs. Ingress

As we define labels for pods in the Pod Template (spec.template.metadata.labels), we can also group the pods with a certain selector in a Service.

The following code snippet shows an example of a load balancer service:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: my-loadbalancer-service

spec:

# Select pods based on spec.template.metadata.labels

selector:

app: frontend

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 80

targetPort: 8080

type: LoadBalancer

The LoadBalancer type tells Kubernetes to provision an external load balancer. This makes the Service accessible from outside the cluster (using the external IP of LoadBalancer). Then, traffic coming to the Service on port 80 is forwarded to the target port 8080 on the selected Pods, using the TCP protocol.

However, when you have multiple services, you need to create a separate load balancer per service, which may result in extra costs.

So in K8s, you can use another service named Ingress to better handle external HTTP and HTTPS requests based on the paths. In this case, we usually put another load balancer in front of the Ingress, and the Ingress can divide and route traffic to relevant backend services based on defined rules.

The following code snippet shows how we define the routing rules to relevant backend services.

In detail:

- Resolve user requests: When the user types “app.com” in their browser, the DNS will resolve the domain to the IP address of the external load balancer.

- Forward traffic to the Ingress controller pod: We can define a set of rules in the Ingress; for example, the requests to

servicea.app.comshould be forwarded toservice-a. In this case, the request uses the internal cluster IP of the relevant service.

# Part 1: Ingress Controller Service

# Add the load balancer in front of the Ingress controller

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: ingress-nginx

namespace: ingress-nginx

spec:

type: LoadBalancer

selector:

app.kubernetes.io/name: ingress-nginx

ports:

- name: http

port: 80

targetPort: http

- name: https

port: 443

targetPort: https

----

# Part 2: Ingress routing rules

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

name: my-ingress

annotations:

nginx.ingress.kubernetes.io/rewrite-target: /

spec:

rules:

# Rule for Service A

- host: servicea.app.com

http:

paths:

- path: /

pathType: Prefix

backend:

service:

name: service-a

port:

number: 80

# Rule for Service B

- host: serviceb.app.com

http:

paths:

- path: /

pathType: Prefix

backend:

service:

name: service-b

port:

number: 80

You can also check this short video to have an introductory overview of the K8s network.

Storage: Persistent Volume, Persistent Volume Claim and Storage Class

As we listed in the workloads section, Kubernetes supports StatefulSets, which means that the relevant data should be persistent. Kubernetes allows you to attach external storage to pods.

If you are familiar with AWS, think of it as attaching an AWS EBS volume to an EC2 instance. Even if the EC2 instance is stopped or terminated, the data on the EBS volume remains persistent and can be reattached or reallocated when needed.

Unlike EBS, which is attached directly to an EC2 instance, Kubernetes creates an additional layer on top of the pod (which is like the end consumer of the storage) called a PersistentVolumeClaim (PVC) .

A PVC can be derived from a predefined PersistentVolume (PV), where you specify the storage location directly, or from a StorageClass (SC), where Kubernetes handles the interaction with the actual storage and creates the PV behind the scenes.

The first approach is called Static Provisioning, while the second one is known as Dynamic Provisioning. The following are detailed explanations:

1. Static Provisioning: PersistentVolume (PV) + PersistentVolumeClaim (PVC)

Page Source: Persistent storage for Kubernetes

Page Source: Persistent storage for Kubernetes

In this approach, we create a PV that defines the actual storage. Then, we create a PVC that binds to the predefined PV.

# Define PV

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolume

metadata:

name: static-pv

spec:

capacity:

storage: 5Gi

accessModes:

- ReadWriteMany

persistentVolumeReclaimPolicy: Retain

hostPath:

path: "/mnt/data"

storageClassName: ""

---

# Define PVC

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

metadata:

name: static-pvc

spec:

accessModes:

- ReadWriteOnce

resources:

requests:

storage: 5Gi

volumeName: static-pv

storageClassName: ""

2. Dynamic Provisioning: StorageClass (SC) + PersistentVolumeClaim (PVC)

Page Source: Persistent storage for Kubernetes

Page Source: Persistent storage for Kubernetes

In this approach, we define a StorageClass to specify the provisioner and parameters for dynamic storage provisioning. Then, we create a PVC that references the StorageClass. K8s uses the StorageClass to automatically create a PV that meets the PVC request and binds them together.

# Define SC

kind: StorageClass

apiVersion: storage.k8s.io/v1

metadata:

name: efs-sc

provisioner: efs.csi.aws.com

parameters:

provisioningMode: efs-ap

fileSystemId: fs-92107410

directoryPerms: "700"

---

# Define PVC

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

metadata:

name: sc-pvc

spec:

accessModes:

- ReadWriteMany

resources:

requests:

storage: 5Gi

storageClassName: "efs-sc"

With these two volumes created, we can attach them to a single pod. All pods created by the Deployment will share these two PVC.

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment # or StatefulSet for stateful applications

metadata:

name: example-deployment

labels:

app: frontend

env: production

spec:

replicas: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

app: frontend

env: production

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: frontend

env: production

version: v1

spec:

volumes:

- name: sc-storage

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: sc-pvc

- name: static-storage

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: static-pvc

containers:

- name: mycontainer

image: myimage:latest

ports:

- containerPort: 80

volumeMounts:

# Mount for the PVC from the storage class

- name: sc-storage

mountPath: "/usr/share/nginx/html/sc"

# Mount for the PVC from the static PV

- name: static-storage

mountPath: "/usr/share/nginx/html/static"

Advanced: Single Attach vs. Multi Attach

If multiple pods are needed in our deployment and they may need to write and read simultaneously, we cannot mount a single PVC with a ReadWriteOnce setting if the pods might be scheduled on different nodes. This is because ReadWriteOnce means that the volume allows only one node to read and write at a time.

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

metadata:

name: sc-pvc

spec:

accessModes:

- ReadWriteMany

resources:

requests:

storage: 5Gi

storageClassName: "efs-sc"

Explanation of three types of accessModes:

- ReadWriteOnce (RWO): Can be mounted as read-write by a single node.

- ReadWriteMany (RWX): Can be mounted as read-write by many nodes.

- ReadOnlyMany (ROX): Can be mounted as read-only by many nodes.

So, we should be careful when selecting the backend storage system. For example, AWS EBS mainly supports single attach (which means it should only be attached to a single consumer), while AWS EFS natively supports multi attach.

Note: In AWS, the multi-attach feature is available on specific volume types, such as high-performance storage types io1/io2. For more information on how to use an AWS EBS volume in Kubernetes, check this documentation.

Also, as you may remember, for a StatefulSet each pod gets a unique identifier in sequential order. With volumeClaimTemplates, each pod will also get its own unique PVC, and the PVC names are generated based on the template name service name and the pod’s ordinal.

In the following code snippet, for the first pod (ordinal 0), the first PVC based on the storage class will be sc-storage-example-statefulset-0 and the second PVC derived from the static PVC will be static-storage-example-statefulset-0.

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: StatefulSet

metadata:

name: example-statefulset

labels:

app: frontend

env: production

spec:

# ServiceName is required for stable network identities

serviceName: "example"

replicas: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

app: frontend

env: production

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: frontend

env: production

version: v1

spec:

containers:

- name: mycontainer

image: myimage:latest

ports:

- containerPort: 80

volumeMounts:

- name: sc-storage

mountPath: "/usr/share/nginx/html/sc"

- name: static-storage

mountPath: "/usr/share/nginx/html/static"

volumeClaimTemplates:

- metadata:

name: sc-storage

spec:

accessModes: ["ReadWriteOnce"]

# For dynamic provisioning

storageClassName: "io1-storage"

resources:

requests:

storage: 5Gi

- metadata:

name: static-storage

spec:

accessModes: ["ReadWriteOnce"]

# For a static PV

storageClassName: ""

resources:

requests:

storage: 5Gi

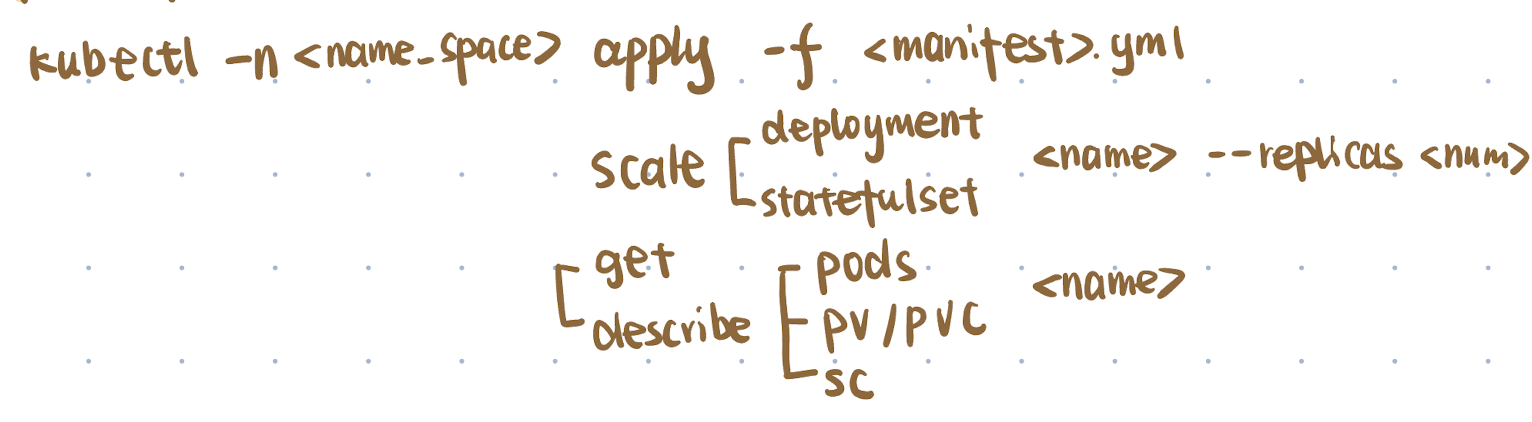

Apply Changes Using kubectl

There are three major categories of kubectl commands:

- Start the pods or update the pods

kubectl apply -f <manifest.yml> - Scale up and down the number of pods

kubectl scale deployment/statefulset <name> --replicas <number> - Monitor services

kubectl get/describe services/pods/pv/pvc/sc <name>

Want to Learn More?

If you have a basic understanding of Docker, you can first watch this video Container Orchestration Explained to understand why we’d rather use Kubernetes, not Docker Compose, for container orchestration.

Then, I recommend watching Kubernetes Explained for a high-level understanding of Kubernetes.

If you are interested in the architecture part, you can also check out these videos:

Then, to get hands-on experience, you can follow this course from DataCamp: Introduction to Kubernetes.

- For the storage section, I found that the article Persistent storage for Kubernetes explains the necessary concepts clearly.

Have fun learning Kubernetes!