Chips, Change, and Challenges: Notes on Reading The Intel Trinity

Chips have become an indispensable part of our daily lives. Thanks to the development of Moore’s Law, what were once huge computers occupying an entire room have evolved into portable and more powerful electronic devices. However, the advancement of Moore’s Law did not happen in a vacuum; it was underpinned by the pioneering efforts of the entire semiconductor industry, notably including Intel.

The first section begins with the origins of Silicon Valley, where William Shockley invented the transistor but failed in management, leading to the departure of a team of talents (also known as the “Traitorous Eight”) who founded Fairchild Semiconductor. The invention of the integrated circuit led to Fairchild’s significant success. However, due to poor management at Fairchild’s parent company, another wave of talent departures ensued. Among those who left were the original Traitorous Eight, including Noyce, Moore, and their subordinate at Fairchild, Grove, who are key figures in Intel’s history, often referred to as the “trinity.”

The second part starts with the childhood stories of founders Noyce and Moore, discussing how Intel, in the 1960s, took a leading position in the memory chip market through the upgrade of existing technologies and the development of new ones, such as Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM).

The third part details the development of the first microprocessor, the 4004, and the breakthrough 8008 microprocessor (which continues today as the x86 architecture). It also highlights the importance of strategic business transformations at critical stages: Intel foresaw and invested in new microprocessor projects while reaping profits from its “cash cow” memory products. Additionally, the section covers how product and marketing synergies were utilized, like cultivating the market through seminars and training manuals when there was insufficient customer awareness.

The fourth part addresses how Intel responded to the memory and microprocessor crisis in the early 1980s. Intel creatively introduced the “Operation Crush” marketing strategy to reclaim market share taken by the Motorola 68000 chip, offering complete microprocessor solutions based on customer needs, and survived the memory market downturn through salary cuts and overtime. Intel’s collaboration with companies like IBM revolutionized the PC market: IBM’s use of the 8088 chip in personal computers and other manufacturers like Dell and HP adopting the Wintel architecture (Microsoft Windows operating system/Intel x86 processor). This section also includes Grove’s rise to power, Intel’s ventures in consumer electronics (such as watches), AMD’s role as Intel’s “second source,” the trade war between Japan and the U.S. in the memory sector, and Silicon Valley’s interactions with the government (supporting the semiconductor industry, reducing capital gains taxes to encourage venture capital growth).

The fifth part discusses how Intel addressed the market crisis caused by the design flaw in the Pentium chip. Initially, Intel applied an engineering mindset (deeming it a rare flaw occurring only once in 9 billion division operations and not promptly addressing consumer replacement demands) before shifting to a consumer-focused approach (symbolizing reliability with “Intel Inside” and spending $450 million to replace products for consumers). The section also touches on Intel’s response to the Federal Trade Commission’s investigation influenced by Microsoft’s antitrust lawsuit.

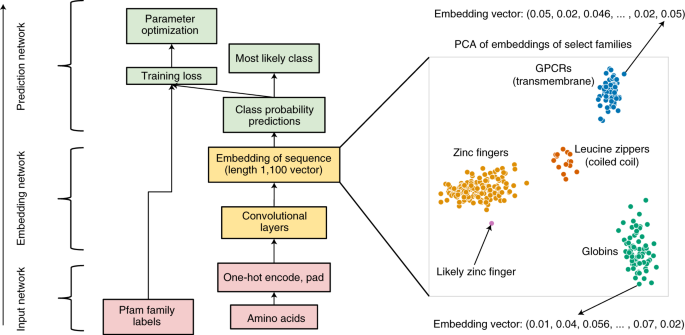

The sixth part provides an overview of the era under Barrett and Otellini after Grove stepped down, noting that “a great operations expert does not always make a great CEO. The former requires exceptional skills, while the latter needs great vision.” Intel faced challenges in both the flash memory and microprocessor sectors, particularly with the increasing use of ARM in mobile devices and cloud computing servers. Kevin Xu’s article in “Interconnect” discusses the tripartite structure of ISA, comprising Intel’s x86, ARM, and the open-source RISC-V. The blog also includes discussions worth reading about the open-source framework RISC-V.

For further reading:

- Direction one: To understand the history of semiconductor development, refer to the appendix “History of Electronic Products Evolution” in “The Trinity”; for digital circuits, “Code,” “The Man Who Knew Too Much: A Life of the Genius Shannon,” and “The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great American Innovation” Chapter 7. The invention of the transistor and the introduction of silicon can be found in “The Idea Factory” Chapters 6 and 10.

- Direction two: The semiconductor industry operates in three models: IDM (design + manufacture), Fabless (design), and Foundry (manufacture). Intel is a typical IDM, Apple, which designed the M1 chip, is Fabless, and TSMC, which manufactures for Apple, is a Foundry. TSMC can be explored through Morris Chang’s autobiography, speeches, and the Acquired podcast about TSMC (equipment manufacturers like ASML in the Foundry sector are covered in “The Making of ASML”).

- Direction three: Books by Grove, a key figure at Intel, such as “Swimming Across,” “Only the Paranoid Survive,” and “High Output Management,” offer insights into his journey from fleeing Hungary to leading strategic transformations at Intel and his still-relevant management experiences.