Fragments of Travel from July 2022 to October 2022

“Remember what you see before your eyes, fix your gaze on a spot, remember its appearance.”

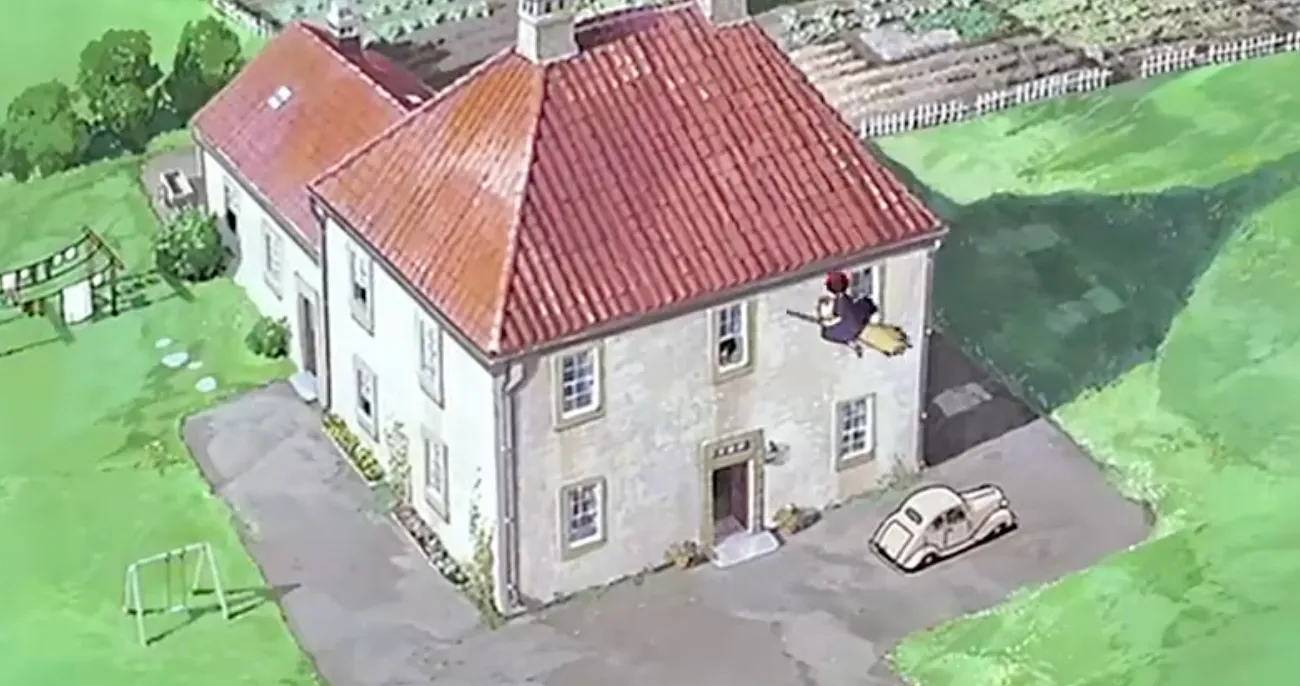

Before talking about travel, let’s talk about Hayao Miyazaki. Those who have seen “Kiki’s Delivery Service” may remember the house where the black cat doll was delivered. Its prototype is located on the Åland Islands in Finland.

Toshio Suzuki of Studio Ghibli recounted that when they visited Finland in 1988 and saw the prototype of this house, Miyazaki was quietly appreciating it. Suzuki, who was taking photos, was scolded by Miyazaki for being “too noisy.” Soon after returning to Japan, Miyazaki, while creating “Kiki’s Delivery Service,” drew the house from memory and even asked Suzuki to compare it with the photos. Mr. Suzuki recalled:

Relying solely on memory, like if you remembered 10 or 15 such details at that time, but after a year and a half, you probably can only clearly remember seven or eight, leading to parts of memory being fragmented or vague. The vague parts have to be filled in with imagination. In other words, the parts that left the deepest impression on you become the main parts of the work.

Thus, an original building was born. This is something that cannot be achieved with photo creation. Photos can only record reality as it is, only memory can create novel works. I was also influenced, and I try not to carry a camera when sightseeing. If you look through the viewfinder, you can’t observe the scenery well. I think it’s more important to use your own eyes to observe and remember.

This story, seen before departure, also reminded me to put down my camera more during the journey, to observe more intently.

The following are some fragments of travel recorded from the northeast to the northwest, from the central plains to Jiangnan, and then to the southwest.

Nature Section

Hiking

“Lonely Planet In Xinjiang” mentioned that the Kanas ring hike “can be considered top-notch in scenery, beginner-friendly, not too physically demanding, but surely a feast for the eyes.” As a hiking novice, I chose the easiest route among the three, “Baihaba-Kanas.” The luggage was carried by guides and horses accompanying the team, and the total 20KM journey still took a full eight hours. Upon reaching the destination, the working uncle and teammates chatted and asked us where we came from and how long it took. After hearing it, they commented, “Travel is indeed suffering.”

But the scenery along the way made all the fatigue and sunburn seem worthwhile. When moving quickly in a car, the scenery always flashes by. But when hiking, everything is close to you: forests and grasslands within reach, constant three-dimensional chirping of insects and birds, casually grazing cattle, freely running horse herds, dogs of various styles…

One extra surprise in Kanas came from a short walk from the visitor center back to the new village. After the tourists dispersed, in the scenic area with few people, under the setting sun, the river shimmered, where you could sit by the bank, turning stones and listening to the water; walking through the grasslands, the soft light passing through the flowers cast a soft glow and stretched the shadows of the trees obliquely. Like mentioned in “On Walking”: “Walking is actually a child’s game, allowing us to be amazed anew at the clear weather, the bright sunshine, the lush trees, and the blue sky.”

This wonder for nature may not only be found in faraway places but also in everyday life.

From the fourth summer of living in Shenzhen, I often went to the park. Once during a downpour, I happened to be in the woods and heard raindrops hitting the trees of different heights and rebounding among them, eventually falling on the nearby grass. Accustomed to the monotonous rain sound on the concrete ground, I realized that rain could sound so layered; in the fifth spring, mostly working from home during the lockdown, I went to the park on weekends and saw trees full of yellow leaves, only then realizing that the season for leaves to fall in this southern city is in spring. Later, I went a few more times and saw these trees from sprouting new leaves after shedding to the new green of early summer.

Man and Nature

Speaking of Kanas to Baihaba, it is a well-established hiking route. The obvious tire and hoof marks mean it’s hard to get lost, but it also indicates significant past human traffic and their left-behind waste—evidenced by the three large bags of plastic garbage collected by teammates along the way.

Later, reading Li Juan’s “Sheep Road Trilogy,” I realized that traditional Kazakh nomads would not do such things: to avoid a large herd of sheep eating away the grass along a specific route causing environmental damage, nomads would take different routes when migrating, even if these variable routes might have to go through very rugged terrain; each time they moved, they would not leave any trash behind, and the practice of moving regularly was itself a way of protecting nature: “To let the earth rest and recover, they keep moving.”

Li Juan also mentioned her mother’s early years of picking wild fungus in the mountains. Later, many outsiders flooded in: “In addition to picking fungus, they started digging ginseng, cordyceps, garnets—plundering everything that could be sold for money without restraint. The mountainside and forest edges became a mess… People started to sneak down the mountain to sell game, and some even brought explosives into the mountains to fish in high mountain lakes.”

But the local nomads would never randomly pull up the grass for cattle and sheep, nor would they hunt wild animals for food. Li Juan said that the nomads “are probably the ones who live in the closest and purest connection with nature, needing the most conscious and firm environmental protection awareness, willing to live on an equal footing with all things, rather than acting as the master of all.”

In contrast, the garbage scattered along the banks of Kanas’ Fairy Lake is a cause for shame. For travelers, at least, they can refer to the concept of “responsible travel” often mentioned in “Lonely Planet,” such as: “Don’t litter: use biodegradable products and try to bring back the trash generated during rural and outdoor travel to the city for disposal.”

Humanities Section

Citywalk ranks top among my favorite ways to explore. It builds a three-dimensional sense of reality step by step from a flat map, and walking on foot always uncovers unexpected aspects of attractions. As mentioned in “Why We Walk”: “Strolling is the best way to understand a city. During driving or riding, you can’t feel the city’s mood, but walking allows you to understand all the dust and glory of city life: the smells, the sights, the footsteps on the sidewalks, the jostling of people, the flashing street lights, and the snippets of conversation of passersby.”

Ethnicity

In a small city in southern Xinjiang, waiting for the night market to open, I stumbled upon a local square dance gathering. In the center of the pavilion was the dance area, surrounded by several layers of spectators. Unlike the lively and exercise-oriented square dances I’ve encountered in mainland China, the dances here were more like light social interactions. People would comfortably change their dance moves with the rhythm of the music, and at the end of each song, everyone would bow to their partner and then invite the surrounding onlookers to dance. Of course, if you’re willing, you can also dance freely.

In the old city, dominated by Uyghurs, the few Han tourists always received special attention. The elderly would open up the front row, signaling us to stand forward, and during the interlude of the song, repeatedly invite us onto the stage. The tourists who eventually went on stage received special care from their dance partners, but no matter how hard they tried, it was difficult to match the fluidity inherent in Uyghur dancing. Interestingly, the next day at the Yarkand Khan’s palace watching the performance of the Twelve Mukams, I found that the most active dancers from the previous night were all performers on stage.

In Mangshi’s Jingpo square dance, it felt more like a simplified version of the grand Munao Zongge Festival. The leading man wore white and carried a long knife-like prop, the women waved fans, followed by rows of men and women, young and old: grandpas with bandages on their ankles, grandmas carrying curious toddlers, pregnant women leading small children… All followed the lead dancer, changing formations and dance moves with the music, and there were unified shouts at specific beats.

Li Juan described Kazakh nomadic dancing as “an instinct—controlling one’s body, displaying desired beauty, knowing oneself, understanding oneself, discovering oneself—dancing is an act of self-discovery.” Watching these free and happy ethnic dances, I always felt a joyous power, which is probably why Uyghurs invite tourists to join, and why I instinctively wanted to join the Jingpo dance.

Religion and Belief

During a Citywalk in Xi’an, arriving at the mosque just before prayers began, a tourist chatted with an elderly worshipper, who patiently explained the prayer process, the passing bathhouse, and the use of the clock hanging in front of the prayer hall.

Later, just before the prayers were about to start, a little boy around six or seven years old ran in, his bright yellow cartoon slippers standing out among the deep gray shoes of the adults. After the prayers, the white-hatted and white-clothed worshippers dispersed quickly, and the mosque, briefly noisy, was left with only the Imam watering plants under the setting sun and a small orange cat darting about.

For them, praying five times a day naturally integrates into their daily life, and this religious practice continues to be passed down with the participation of the younger generation.

Compared to religion, beliefs are more commonly seen in folk culture. As Chiang Hsun said:

“Belief is a broader term, and strictly speaking, it is a different system from religion. Religion is more rigidly defined, with a complete system, starting from Genesis, how the universe was created, where life comes from, where it goes…

the process of practice and the rules are very comprehensive. There aren’t many that can be called religions in the world, such as Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, etc. Beliefs are more numerous, like Mazu and Guan Gong; they are not strict religions, but they are beliefs.”

In Yunnan, one naturally notices traces of beliefs everywhere, from the Benzhutemple worshipped in Dali’s Bai ethnic villages, the Kuixing Pavilion still used for students’ blessings, to the reserved incense spots in homes, Jiamazhi paper burned for sacrifices on specific occasions (like the gods of mountains, forests, grass, thunder, land, etc.), and the creation myths passed down orally and still believed by various ethnic groups (like the De’ang people who believe they are descendants of tea plants)…

The poet Yu Jian mentioned the belief of “animism” among Yunnan’s ethnic groups: “According to Qing dynasty documents, over 140 different ethnic groups were recorded in Yunnan. They believe in animism, the land is not only the land of people but also that of gods. And this god is not a single idol, but almost everything outside of humans – forests, rivers, grass, wild animals… all part of a vast system of gods.”

“Those who are disobedient, seek but do not find blessings”

Thinking about the self-imposed restrictions of Kazakh nomads, like not digging up grass and regularly moving, and the local belief in Yunnan of “animism,” I wonder if both are extensions of respect for nature born from belief. This is probably what Chiang Hsun meant by belief letting people “know there’s an incredible force above guiding them, teaching humility.”

Later, in Weishan’s Jiamazhi shop, chatting with the owner, the elder first showed a carved board of the God of Wealth and the deity overseeing marriages, which he probably thought were more appropriate for the reality-focused outsiders :)

Philosophy of a Sufficient Life

In Dali’s Citywalk, what I felt more was leisure. In narrow alleys, the car behind an elderly person didn’t honk impatiently but followed slowly behind.

Once, while taking shelter from the rain by the roadside and chatting with a lady selling milk fans, she went to get lunch and passed by many tourists. Talking to her later, she said, “Earn what you can, and don’t fret over what you can’t. Just let nature take its course,” without any regret or sorrow for missed opportunities.

Then there were the Dali shop owners who would take holidays off or close early on rainy days, causing inconvenience to tourists, as complained about by a fellow female traveler. In the small town of Weishan, the capriciousness of the owners was even more apparent: popular noodle shops would only stay open until sold out, usually only till noon, often disappointing day-trippers. From a conventional economic perspective, to make more money, hiring more staff to extend opening hours and expanding the shop would be natural, but they deliberately chose not to.

Chiang Hsun in “Ten Lectures on Life” spoke of Paris’s philosophy of “enough” happiness: “I think the greatest joy of returning to Paris each time is to rediscover so many people’s confidence. Every corner has someone’s confidence, quiet, not wanting to disturb others.

For example, the ice cream shop owner, he sells dairy-free ice cream, and for decades, there’s always a long queue outside his shop. But he never thinks of opening more branches. He seems to have a feeling of ‘enough,’ which is a difficult philosophy: ‘I am happy doing this, and everyone who eats my ice cream is happy, so, it’s enough.’”

I think this philosophy of happiness also applies to these capricious shop owners.

Scattered fragments from Citywalk:

- In Kashgar’s old city, I heard conversations from above; looking up, I saw children from two households chatting across the alleyway;

- In Mangshi village, I saw a funeral arrangement chart on the wall, likely a result of neighborhood cooperation needed for funeral tasks; and saw many names consisting of a surname followed by a number like Yang Two, Xian Four, Jin Five… probably Han Chinese names reported in birth order during identity registration;

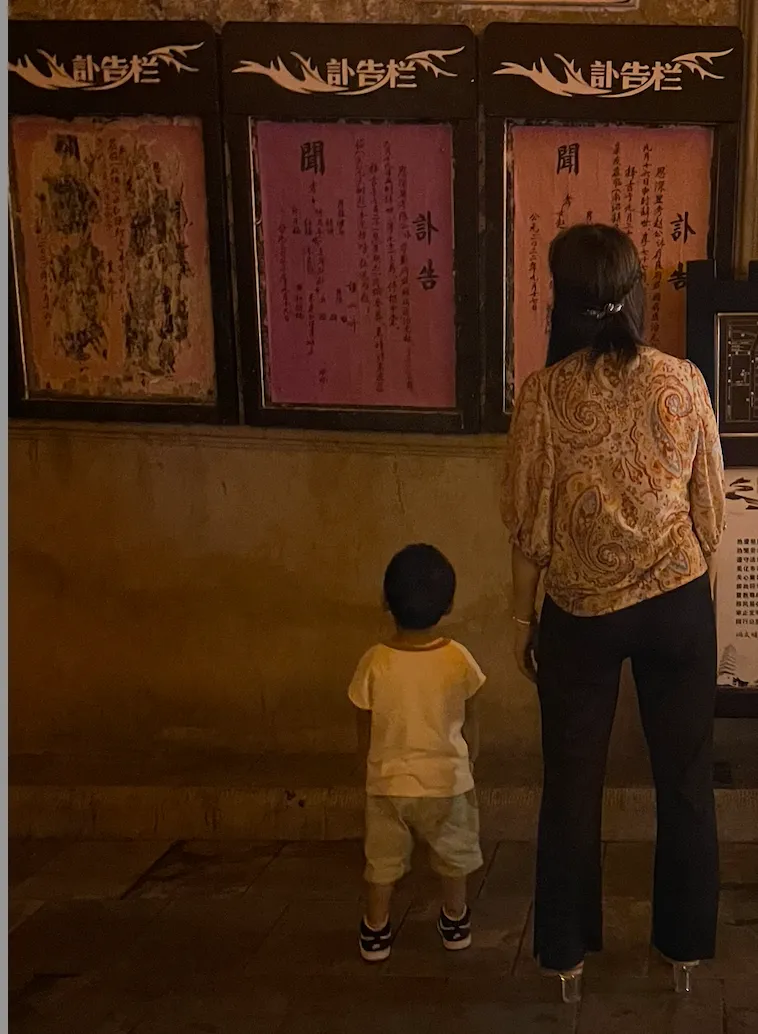

- In Weishan, people post obituaries in the main street notice board after someone’s death. Couplets about the death are posted on house doors; three years after death, a couplet marking the end of mourning is added. Near the city gate, the coffin shop is next to lively snack shops, “This living ancient city seems to have no taboo in discussing death.”

And those fleeting encounters with passersby: from learning to invest from zero to save an annual travel fund, taking up heavy hiking when free, a Shanghai girl who just learned horse riding in Inner Mongolia, a 70-year-old who followed his parents to Xinjiang in the 1950s, a Shenzhen sister who hitchhiked across Xinjiang with her son, a Beijing girl who resigned from official media because the news became uninteresting, a Heilongjiang aunt who retired before her husband and traveled alone, a Shenzhen elder who retired early, backpacked abroad for years before the pandemic, and now lives in a small town writing travelogues about Africa…

But more often, it’s what I, as an observer, saw. Li Zishu, author of “Vulgar Land,” once said that she would be the only one not scrolling on her phone in the subway car because guessing the lives of those around her is more interesting than scrolling on her phone. She would imagine their states and backgrounds.

Later, during my travels, I consciously put down my phone to “read” the people around me. Below are some “human observation records”:

- Waiting in Urumqi’s Consulate Lane for the baked naan with lamb, men knead dough in the back, a little boy guards the naan pit, also taking money and handing out tissues. I arrived earliest, then many people came, and finally, the queue around the naan pit was indistinct. When the naan was ready, I saw an old grandma and grandpa in front, silently ready to let them take first. But a nearby Uyghur elder said something in Uyghur to the boy, who asked me how many I wanted and handed me the naan first, a pleasant surprise. Btw, their lamb naan is delicious.

- Xi’an Museum has a special exhibition hall for Buddha statues. I passed it several times and saw children praying to the tall Buddha statue in the middle. When looking at a Guanyin statue, a little girl asked her mother if it was Tang Sanzang (it had a crown and necklaces, looking a bit similar), her mother said it was a Bodhisattva, and the girl regretfully said she guessed wrong again. Her mother said it’s okay, she’ll get it right next time.

- While queuing for mahua and oil tea, an elder grumbled that only tourists came to eat here. The lady owner heard and was not pleased: “It’s your first time here,” pointing to a lady waiting nearby without queuing, “This auntie lives on the street ahead, she comes to take away three portions every day.” Although it became a tourist hotspot, she still wanted to prove her shop was loved by local neighbors.

- Next to the must-eat list of zenggao in Huifang, there’s another zenggao shop more popular with locals. Resting by the roadside, I saw people stopping their electric bikes to take away zenggao. Watching a brother and sister come, the sister handed ten yuan to the owner, who said a large one for ten, a small one for five, asking if they wanted one large or two small. After several questions, the siblings were unclear, then asked about their mother/where they lived, finally realizing they might be children of the neighboring bun seller. The owner eventually gave them two small ones, complimenting their good looks. The siblings hand in hand took two boxes of zenggao home.

- A three to four-year-old boy sat by the airplane window, with his mother and father beside him. Standing next to his mother’s seat, the boy said, “Mom, I want a hug.” His mother replied, “You’re grown up now and have your own seat; you can’t sit on mom’s lap anymore.” The boy said, “But I’m still a little baby.” His mother responded, “Well, come sit before we take off.” Even children who always want to grow up sometimes wish to exercise their baby privileges.

- At the subway station, there was an advertisement for “Cute Baby Mobilization,” featuring large photos of infants and blessings from parents. The wishes were mostly for the children to grow up happy, healthy, and safe, with one wish stating, “I hope you can sleep until you wake up naturally every day.” It made me wonder, in the real process of growing up, beyond these basic expectations, are there more expectations that emerge, such as attending a good school, finding a good job, or getting married and having children early…

- In the bustling Xiyuan Temple, I saw a family of three come to pray. Each person held incense, first raising it above their heads towards the main hall to bow three times, then turning to bow in different directions. The little boy, after each bow, would sneak a glance at his father to see when he would turn, following suit when his father did. Someone said this might be the process of learning social norms.

- Resting near the restroom at Canglang Pavilion, a mother insisted that her daughter, who looked at least eight years old, go to the toilet. The daughter somewhat rebelliously said several times she didn’t need to go, but the mother, while packing up, seriously told her to try, suggesting she might need to after all. Later, during a carpool journey, I chatted with an auntie who talked about her daughter who loved drawing, “But her dad and I didn’t understand it, so we tore up her drawings every time we saw them. She ended up studying something else in college.” I felt sad for the little girl forced to go to the bathroom and the stranger whose drawings were torn up.

- At the high-speed train station, waiting in line to board, a girl was excitedly talking on the phone, sharing with a friend, “I’m getting married. There’s a guy I’ve known for two years. Recently, he mentioned he’s being pressured to marry too, and so is my family, so we decided to get married. Next time I come back, we’ll get the certificate.” The friend probably asked about the man, and the girl said he’d been in the army for nine years, so he must be responsible. This was a glimpse of contemporary marriage’s expedited nature.

- At the supermarket entrance, there was a little girl, around two or three years old, sitting in a paid ride-on car, smiling happily. A delivery man in a yellow uniform, her father, sat on the backseat chair, watching his daughter intently, so absorbed that he didn’t even notice the passersby staring at him.

- During lunch, a bookstore employee talked about her daughter, who had a childhood sweetheart aspiring to be a police officer. Once, while watching TV and seeing a police officer sacrifice, the little girl told her mother she would tell her friend not to become a police officer.

- A very tanned, thin old man, nearly bent at a 90-degree angle, walked across the street carrying two full snake-skin bags. He stopped to rummage through a roadside trash can, found nothing of interest, and continued towards the next can.

- These observations were never part of the meticulous itineraries of tour groups, but during leisurely travels, they constantly offered chances to glimpse and observe more vividly the destinations.

Regarding Xinjiang, I also recalled, beyond the tourist perspective, a post on Weibo about the head of the Economics Department at Johns Hopkins University going through the process of changing his Xinjiang passport, perhaps representing the real life experiences of locals in Xinjiang.

History Section

The order of this trip wasn’t specifically planned, but in hindsight, it could be reviewed in a certain chronological order: first to Xinjiang and Xi’an, prospering from the overland Silk Road; then to Jiangnan, flourishing during the Ming and Qing dynasties; and finally Yunnan, gradually deepening its interaction with the Central Plains from a relatively independent southwestern frontier (local intellectuals participating in imperial examinations, Han customs brought by border defense such as coffin burials), as well as the Southwest United University and the Burma Road during the war.

Two points left a deep impression: one is the jar lamps unearthed in Xi’an, Nanchang, and Yangzhou, with the most ingenious design in the Shaanxi History Museum, but the basic principle is the same: lampshades that can rotate directions and water to dissolve smoke.

Another point was the special exhibition “The Face of Civilization” at the Wuzhong Museum, primarily featuring artifacts from the Eurasian continent, with a special mention of the commonality in the development of civilizations in the Mediterranean, Western, and Central Asia, such as the sculptures and decorations from the 20th century BC, and the Greek and Indian style sculptures from the Gandhara region of the 6th century.

“The Invitation to Linguistics” discusses the significance of reading fictional stories: “When we use this method to observe the lives of other groups of people at any time and place, we will be amazed to find that they are flesh and blood humans just like us. This discovery is the foundation of all civilized interpersonal relationships.” In a sense, the artifacts in museums serve a similar purpose.

In terms of geographical latitude, moving away from ethnocentrism to understand others, I’m reminded of the famous anthropologist and author of “Imagined Communities,” Benedict Anderson’s autobiography, which mentioned the metaphor of stepping out of the coconut shell. In his postscript, he noted:

From this perspective, one can see the value of “area studies,” as long as they are not too urgently guided by the state (Indonesian rebels like to call the state “siluman,” a terrifying ghost). When facing political or economic difficulties, states tend to incite nationalism and a sense of crisis among their citizens. The fact that young Japanese are learning Burmese, young Thais are learning Vietnamese, and young Filipinos are learning Korean is a good sign. They are learning to step out of the coconut shell and start noticing the vast sky above them. This involves the possibility of abandoning egocentrism or narcissism. It’s important to remember that learning a language is not just about learning a way of communication. It is also about learning the thought and feeling processes of a nation that speaks and writes a language different from ours. It is about learning the historical and cultural foundations that constitute their thoughts and feelings, and thus empathizing with them.

The other perspective is to take history as a mirror, to review and understand past events. The author of “Why Did the Japanese Choose War?” in the afterword explained why he wrote the book:

I wanted to understand how Japan, a country that experienced a major war almost every ten years from the First Sino-Japanese War to World War II, justified the reasons for each war to gain public support. The reason for clarifying these facts is that I always had a doubt: if I had lived in that era, would I have been deceived by the state’s rhetoric? I was afraid I couldn’t see through those grandiose words.

…

Every day of our lives, we unconsciously evaluate and judge what happens around us. When evaluating or judging the current state of society, we unconsciously use past examples for comparison. When further projecting the future, we again unconsciously compare past and present examples.

At these times, how many historical facts are stored in the minds of young people, and to what extent have they organized and analyzed these facts? These factors will ultimately influence their judgments of the present and future.

Before the pandemic, on a visit to Taiwan, a volunteer guide at the Taipei City Museum, discussing modern history, asked us if we knew about the “xx uprising.” We shook our heads in bewilderment, and the guide was surprised. It dawned on me later that this part of history might be common knowledge to them. Reflecting further, I realized that in discussions about events in different regions, a lack of understanding of local history can lead to conversations that are not on the same wavelength. For travelers, listening to local history narrated by museum guides opens up different perspectives.

Going further, this is akin to what is taught in “The First Lesson of Hong Kong”: To avoid being deceived by self-righteousness, social sciences often emphasize learning to be a ‘professional stranger’ to transcend daily arguments. Upon encountering a phenomenon, instead of immediately criticizing it, it’s more important to seek the underlying reasons. This approach of making the familiar seem strange is beneficial for both Mainland China and Hong Kong. Many things that Hongkongers might be accustomed to or take for granted actually require more analysis.

From this perspective, it’s advisable to view museum exhibits with a critical eye. For instance, the Tengchong Yunnan-Burma Anti-Japanese War Memorial. The museum showcases and recreates the hardships of the expeditionary force’s battles and the Japanese army’s brutality. However, there are also overlooked details, such as those mentioned by the author of “The Soul of a Great Country.” The father, who had participated in the expeditionary force, was raided during the Cultural Revolution for being “bourgeois… a remnant of the Kuomintang expeditionary force… class enemy…”. These Kuomintang veterans remained unrecognized for many years; and those who survived, who didn’t flee to India or trek back over the Savage Mountain, were ultimately rejected by all sides.

Architecture Section

Tadao Ando, in his twenties, traveled to Europe to study architecture, journeying from the Pantheon of ancient Rome to Le Corbusier’s Notre-Dame du Haut. He later recalled that the depth of understanding gained from reading abstract vocabulary is entirely different from that acquired through firsthand experience.

This experience, not easily attainable through reading alone, is especially apparent in architecture. The changes in light and shadow, the feel of materials, the height of ceilings, and the scent in the air all contribute to the spatial sensation created by architecture, requiring people to be physically present.

How is space created? Apart from the technical aspects of construction we understand, Wang Shu also mentions in “Building a House” that construction requires a sense of taste. “Building a house is like creating a small world,” and “constructing a world depends first and foremost on one’s attitude towards that world.” Gardens, for instance, are typical examples of spaces built with such attitudes.

Suzhou’s gardens, mostly built in busy urban areas and known as urban forests, are not just about recreating nature within these “forests.” The overall layout (like the Yi Studies in the Couple’s Garden Retreat) to the naming of pavilions (such as the “With Whom Shall I Sit Pavilion” in the Humble Administrator’s Garden), the gardens themselves also carry the lifestyle and thoughts of the owner, as Wang Shu says, “The garden maker, the garden dweller, and the garden grow and evolve together.”

For visitors, how can one truly experience the ingenuity of garden design? Refer to “The Garden Maker” by Yu Kuan, who noted that “(gardens) provide a habitat for the garden owner to both wander and reside in - not just a park to be quickly toured and left.” Wang Shu also mentioned, “Gardens are not just visual objects but bodily experiences. Former garden owners lived in the gardens for years, where life was flavorful.”

Appreciating a garden requires patience: sitting in pavilions, observing well-placed borrowed scenery, rocks, and plants; physically experiencing the twists and turns of garden paths or rockeries; changing views as you move, and observing framed views; variations in light and shadow through the windows with the sun’s angle, and the unique features hidden in different seasons/weather: the sound of rain on banana leaves, the fragrance of lotuses in summer, the scent of osmanthus in autumn…

Each garden has its unique features, such as: feeling the contrast between darkness and light at the entrance of the Lingering Garden; experiencing the almost contorted, decomposed space under dim light in the Cui Ling Long of the Canglang Pavilion; the self-growing ivy on the tall walls of the Art Garden Qinqu along with the Taihu rocks; the sense of water extension at the Crane Step Beach in the Yi Garden…

This patient exploration is not only applicable to gardens but also to any art that requires patience to appreciate. Harvard professor Jennifer L. Roberts spoke about an art history course where students had to choose a painting for an essay, but the catch was that they had to spend three hours observing the painting before conducting further research. Roberts believes that only by spending time observing can one notice details, like in “Boy with a Squirrel,” where she took 9 minutes to notice the similarity between the squirrel’s belly wrinkles and the boy’s ear, 21 minutes to see the similarity in the diameter of the cup and the fingers holding the chain, and 45 minutes to find a resemblance between the seemingly random wrinkles on the curtain and the boy’s eyes and ears.

Professor Roberts, in “The Power of Patience,” argues that while vision is generally thought to be direct, simple, and immediate, in fact, the details, order, and relationships in any work of art require time and patience to perceive.

BTW, if the main purpose of visiting a garden is to see the architecture, don’t waste money on night tours; there are more professional places to see intangible cultural heritage performances like Kunqu and Pingtan.

Other: Travel Guides, Luggage, and the Meaning of Travel

Regarding Travel Guides

Chunyin recently shared the process of making travel guides, and the steps are similar: reviewing stored travel guides and Lonely Planet, marking accommodations/attractions/dining on the map, and arranging the itinerary, completing necessary reservations.

Surprisingly, Xiaohongshu proved to be an excellent search engine during the trip, providing detailed information such as museum ticket release times, not available on official platforms, much better than the stock/medical beauty ads common on Weibo. (However, a comparison showed that Xiaohongshu has one of the strictest content moderation policies, where official content recommendations affect the direction of content creation, reflecting Jonathan Blow’s saying “The medium is the message,” where the medium itself impacts content quality.)

Regarding Luggage

Before leaving, I came across a post by Vitalik Buterin (yes, the Ethereum founder) about his one-bag travel experience and browsed Reddit for tips from frequent backpack travelers. Useful insights include: 1) Layered dressing: Prepare quick-dry base layers, warm layers, and windproof outer layers based on destination weather, packing them in compression bags; 2) Volume optimization: Use a universal charger for everything from toothbrushes to electronics; 3) Establishing a travel routine, like Vitalik’s daily tea drinking.

Overall, my luggage wasn’t optimized to the fullest, consisting of a 20-inch suitcase and a backpack. In Dali, I met a Sanya sister who had also been traveling for a long time with her eight-year-old child, carrying a similar amount of luggage, which made me realize that we often don’t need as much as we think when traveling. Maybe in the future, I can achieve one-bag travel. :)

The Meaning of Travel

If I must summarize, the main significance of this trip for me was having ample free time.

As my high school Chinese teacher wrote in a blog before university, “After this longest summer vacation, think about whether you cherished the freedom you once longed for.”

During this longest vacation since adulthood, this luxurious freedom was used to connect with nature, experience culture, contemplate architecture, and more importantly, to continuously converse with myself during the planning and actual travel: Step by step, asking what I want, what I can let go of, what to focus on, and what to ignore in interactions with the outside world.

The end of this journey doesn’t signify the end of these reflections.

According to psychologist Daniel Kahneman, our lives have two selves: the experiencing self and the remembering self. People tend to romanticize memories, forgetting less pleasant experiences, even if they weren’t so good at the moment.

Apart from the glamorous, talk-worthy aspects captured in photos, the trip had its share of unpleasant details: sweating profusely in 40-degree heat while touring gardens, changing beds in overnight sleeper trains dominated by middle-aged men, exhausting walks in museums without proper planning, dealing with minor injuries and illnesses, and having to flexibly change plans due to local epidemic situations and preventive policies.

Moreover, travel itself has been somewhat over-romanticized. Traveling to distant places in itself won’t solve any problems, and being obsessed with ticking off places hardly contributes to intellectual growth.

As stated in “The Invitation to Linguistics”: “Unless one knows what to seek in their experiences, those experiences often prove meaningless. Many people value experience highly… They think: ‘I don’t want to just sit around and read books; I want to go out and do things. I want to travel and gain experience.’ But when they actually venture out, the experiences they gain often offer them no benefit. They might visit London, yet all they remember are the hotels they stayed in and their travel group. They may have traveled to China, but their entire impression of it is merely ‘There were many Chinese people there.’ They might have served in the military in the South Pacific, but all they recall is how unpalatable the food was in the army.”

Rousseau considered travel a vital part of Emile’s education, but this was predicated on Emile already possessing the freedom and ability to observe, coupled with a purposeful intent to explore.

However, even if we don’t know what to look for in our experiences, we can still try to be like Hayao Miyazaki and Toshio Suzuki: put down the camera, observe with our eyes, and feel with our hearts:

Remember what you see before your eyes, fix your gaze on a spot, remember its appearance.

Observe it when it snows, when the grass starts to grow, and when it rains.

You need to feel it, remember its scent, and explore the texture of the rocks as you walk back and forth.

In this way, this place will always be with you.

When you travel far away, you can call upon it, and when you need it, it will be there, in your heart.”